Errors

What happens when you run a Python program?

No matter whether you run Python in a terminal with a shell command like python my-program.py,

or in an IDE with a 'Run' button,

what exactly happens is defined by the three sets of rules that define the language:

- Syntax

- Static semantics

- Dynamic semantics

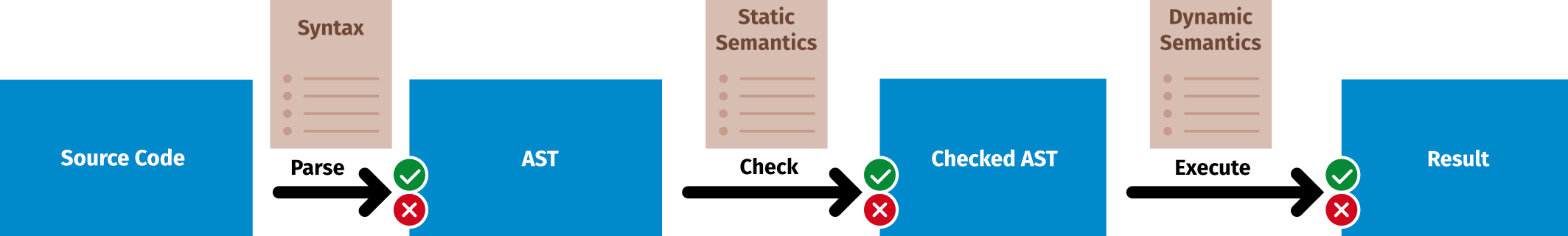

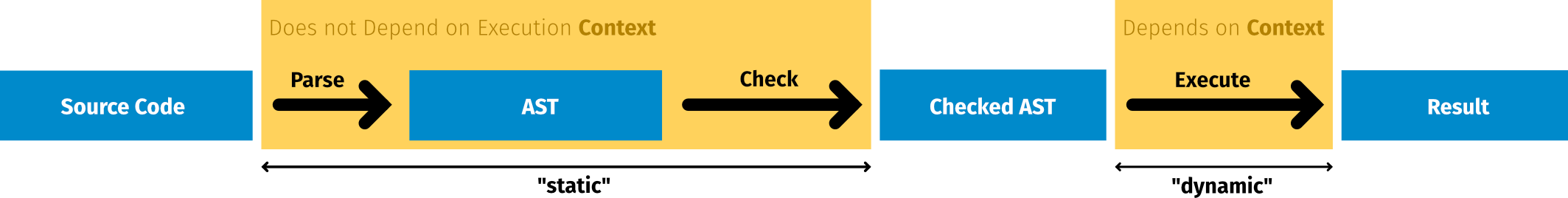

These rules are used to form a "pipeline" that takes in the program's source code (on the left) and spits out the result (on the right) of executing the program.

At each stage of this pipeline, something could go wrong, which will lead to an error.

The Rules of a Language

The syntax rules determine whether source code is grammatically correct. They allow source code (a sequence of characters in Python) to be parsed into a tree structure (an abstract syntax tree, AST).

The semantics rules determine the meaning of a grammatically correct program. These rules are typically divided into two parts: static semantics, which detect syntactically correct programs that do not have a well-defined meaning, and dynamic semantics, which define the precise behavior (or meaning) of programs that are valid according to the static semantics.

While the static semantics rules can prevent many incorrect programs from being executed, they cannot prevent all possible runtime errors. Thus, even after rigorous static semantic checking, some programs may still produce errors at runtime (i.e., according to the dynamic semantics, certain situations are undefined or lead to runtime exceptions).

Parsing (Syntax)

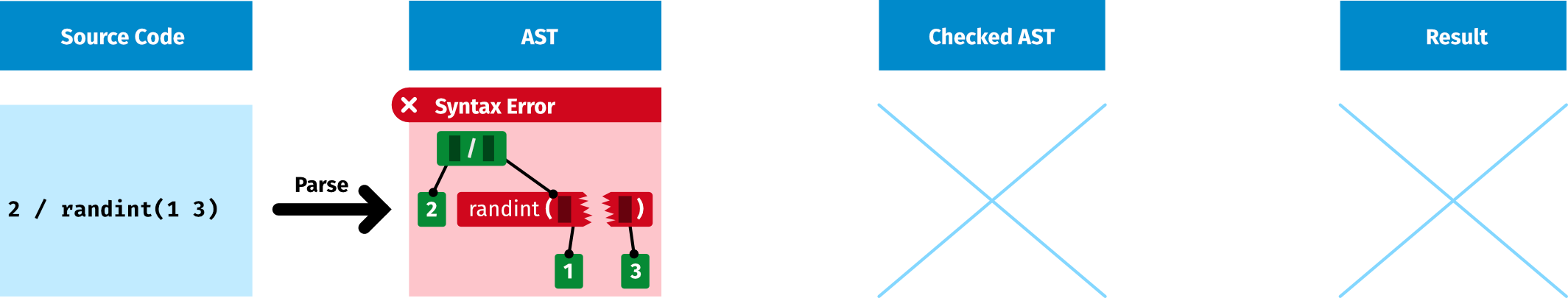

The first step is parsing: converting the source code into an AST.

The source code on the left, 2 / randint(1 3),

illustrates a possible problem:

The Python syntax does not include any rules that would describe how to convert the above source code into a tree. This kind of problem, where code cannot be parsed, is reported as a Syntax Error.

There is no point in executing this source code, because the code doesn't have a valid structure. There is not even a point in checking the static semantics.

This error, the missing comma between arguments of a function call, is one of many possible errors that can be detected based on the rules of the syntax.

Checking (Static Semantics)

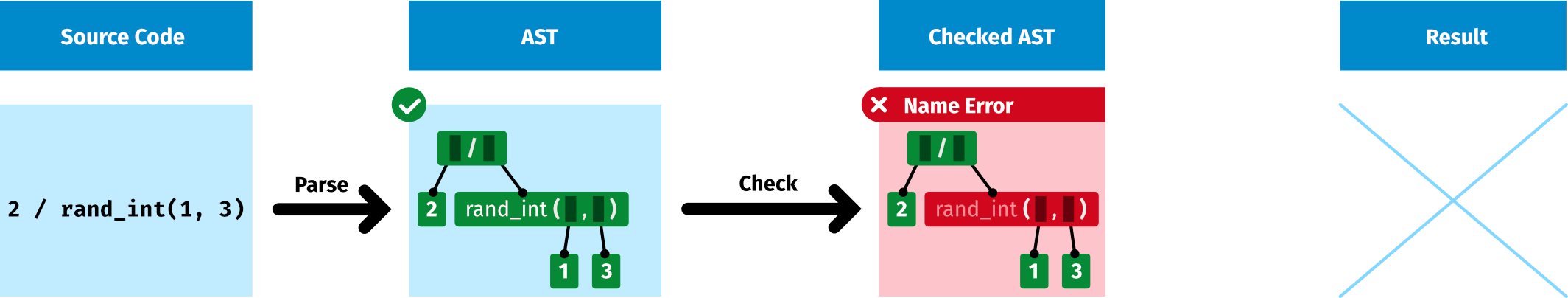

Now let's look at the second step, checking, and an example of what could go wrong:

The checks find a problem in the AST node rand_int(█, █):

Python is supposed to call a function known under the name rand_int,

but nowhere in our program does it say what function that name refers to!

Python cannot call a function named rand_int for which it has no implementation.

No matter how readable the name is in English,

Python needs the actual function, not just a name.

This problem is reported as a Name Error,

which is one of several kinds of errors the static semantic checks will uncover.

This error, the use of a name (rand_int) that has not been defined,

is one of many possible errors that can be detected based on the rules of the static semantics.

Executing (Dynamic Semantics)

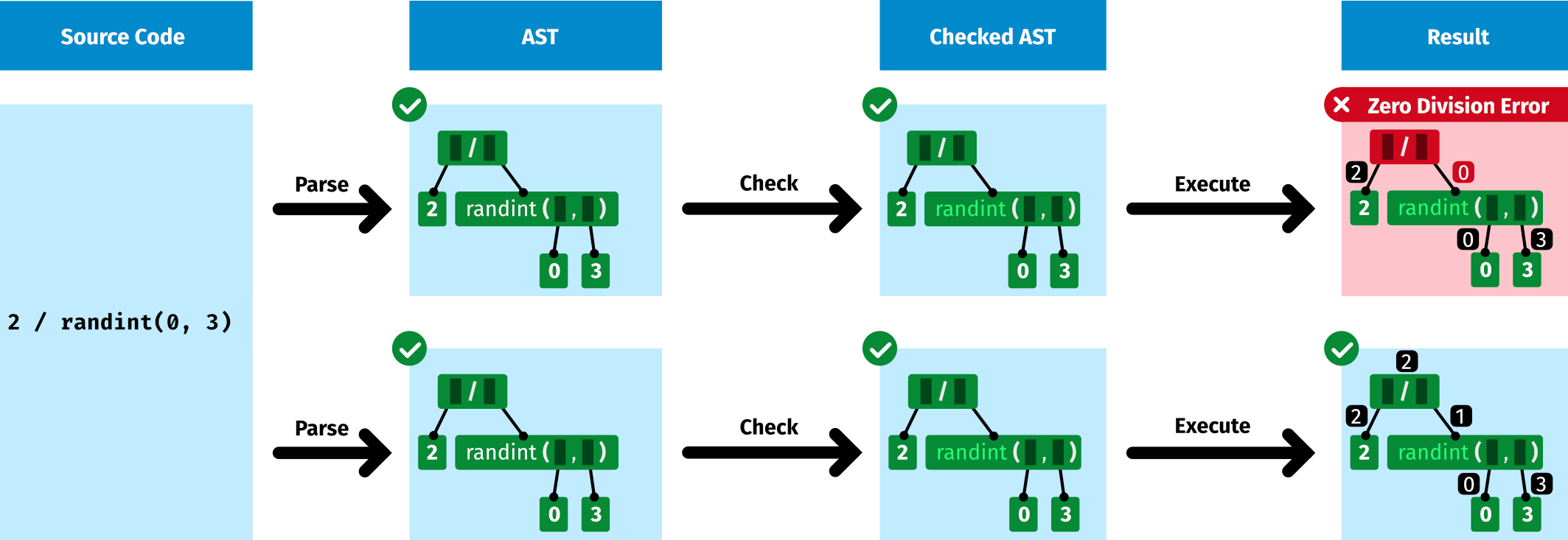

Now let's look at the last step: executing. The following figure shows two scenarios: the first one leads to a failure, the second one to success.

The above source code is syntactically correct and does not violate the static semantics. However, when you run it, sometimes it will cause an error, and other times it will succeed in producing a result. This behavior is governed by the dynamic semantic rules.

The call randint(0, 3) produces a random number between 0 and 3

(inclusive).

If randint returns the value 0,

this will trigger a ZeroDivisionError,

because the dynamic semantics of the division operator says so.

If, on the other hand, randint returns the value 1,

the program execution succeeds,

and the evaluation of the expression produces the result 2.

The expression 2 / randint(0, 3) is buggy: it sometimes crashes.

Errors Depending on Execution Context

Some errors will happen no matter what. Other errors will only happen if you run a program in a specific context. Let's look at our pipeline to see where execution context comes into play:

With execution context we mean everything that affects the computation:

- Whatever the user enters when the program calls input

- Whatever the program reads from files, the network, or anywhere else

- The command line arguments given when launching the program

- Information the program receives from the random number generator, e.g., with the call to randint, like in our example above

Static Analysis

Reasoning about a program without running it, without knowing its execution context, is known as static analysis. It is sufficient to do this static analysis only one time; we do not need to repeat the same reasoning over and over each time we run the program.

Certain Failure

The above code does not depend on the execution context. It does not use random numbers, does not read from files, and does not prompt the user for any input.

We can tell with 100% certainty what will happen when it executes.

It will fail, every time we run it, due to the name answer not being defined.

There is pretty much no point in running this code. We can see that it is broken, so we should fix it first! (If you ask yourself why the RUN button is even enabled in such a situation: Great question! Thanks for playing! We will get there.)

Certain Success

Knowing all the rules of Python, we can tell with 100% certainty that the above code will always succeed.

Maybe?

By looking at the code, without running it, you are unable to tell with certainty whether or not it will succeed! A static analysis is not enough. You need a dynamic analysis: you need to run the program!

Dynamic Analysis

To find out whether an error that depends on the execution context actually happens, just looking at the program is not enough; we also need the execution context, and so we need to run the program. This kind of reasoning is known as dynamic analysis.

If you run this code multiple times, it will sometimes succeed, and sometimes fail.

Given that randint(0, 1) returns 0 with 50% probability,

it will fail in 50% of the cases with a division by 0.

To know whether or not it fails, we have to run and see. Python will report the error at runtime.

The expression 2 / randint(0, 1) is buggy because it sometimes crashes.

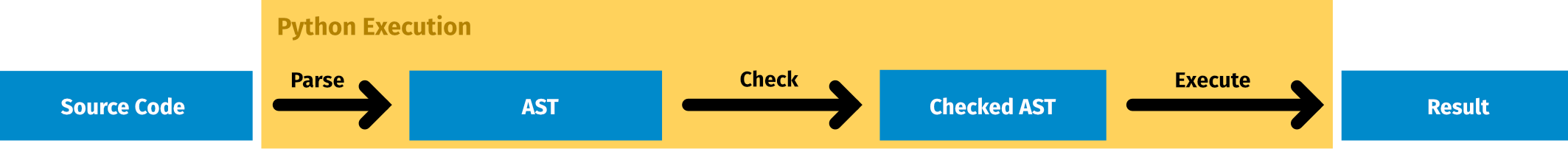

Python Execution vs. Checking

Python on the Command Line

When you run a Python program on the command line, Python parses your source code (and thus checks its syntax), then checks whether it follows the static semantics, and then executes it following the rules of the dynamic semantics.

The following command leads to your code being checked and executed in one go.

python my-game.pyWhen errors happen, it may be hard to distinguish whether they happened during parsing, during checking, or during execution. There is some indication, though. Python usually reports violations of the syntax as SyntaxError. It has various types of errors related to violations of the static semantics, most importantly NameError and TypeError.

Python in the IDE

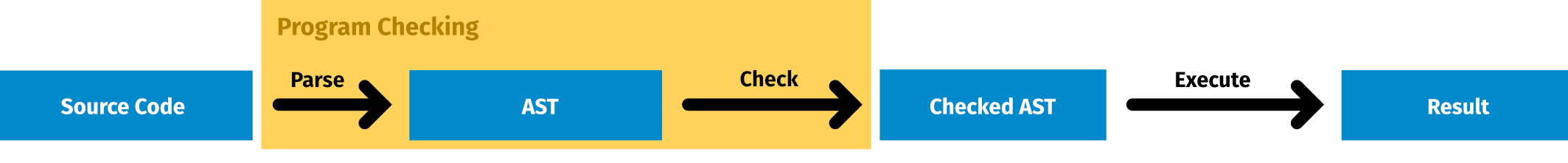

If you work in an IDE (or in this PyTamaro Web platform), the IDE may already check your source code before you execute it.

These checks could happen on request (e.g., whenever you request your code to be "built" or "compiled"), or they could happen live, in real time (i.e., while you are typing the code).

Many IDEs just check the syntax (because that is relatively easy to do). More advanced IDEs also check the static semantics (which requires non-trivial program analyses).

PyTamaro Web

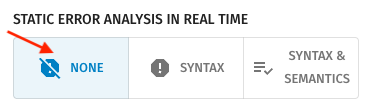

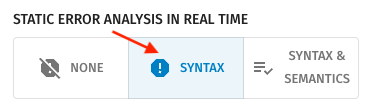

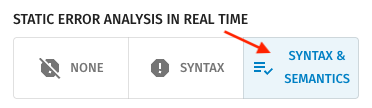

PyTamaro Web reports errors when you run code. Additionally, thanks to its static error analysis in real time feature, it can report some errors already while you edit code.

You can configure whether or not PyTamaro Web performs static error analysis in real time:

- None: No static error analysis in real time (errors are only reported when you run code)

- Syntax: Static error analysis in real time of syntax rules

- Syntax & Semantics: Static error analysis in real time of syntax and static semantics rules

Let's explore how this works! We start with the most basic option: no static error analysis in real time, with errors reported only when you run the code.

Runtime Checking

Whenever you run the program, Python checks all the rules (syntax, static semantics, dynamic semantics).

PyTamaro Web shows those errors in two ways: it displays them as part of the output of the program execution (below the code cell), and it pops up a sticky tooltip at the corresponding location in the source code. That tooltip is annotated with a ⚡️ to indicate that this error happened during execution. The tooltip sticks around until you click the ⊗ icon or edit the code.

Static Error Analysis in Real Time

Let's investigate the three different configurations of static error analysis in real time by looking at the same code cell using all three configurations, one after the other.

No Checks

The following code cell contains three errors. With static error analysis in real time switched off, there should be no red wiggly underlines. You have to think a bit to figure out what is wrong (or you have to run the code, which will cause Python to report the first error it encounters).

Syntax Checks

Now let's use static error analysis in real time to get live feedback on syntax errors.

You should see one red wiggly underline.

Whenever you hover your mouse over the wiggly underline, it pops up a tooltip with the error message. The tooltip disappears when you move the mouse away.

Syntax and Static Semantics Checks

Now let's enable full static error analysis in real time:

The above code cell should now show three errors.

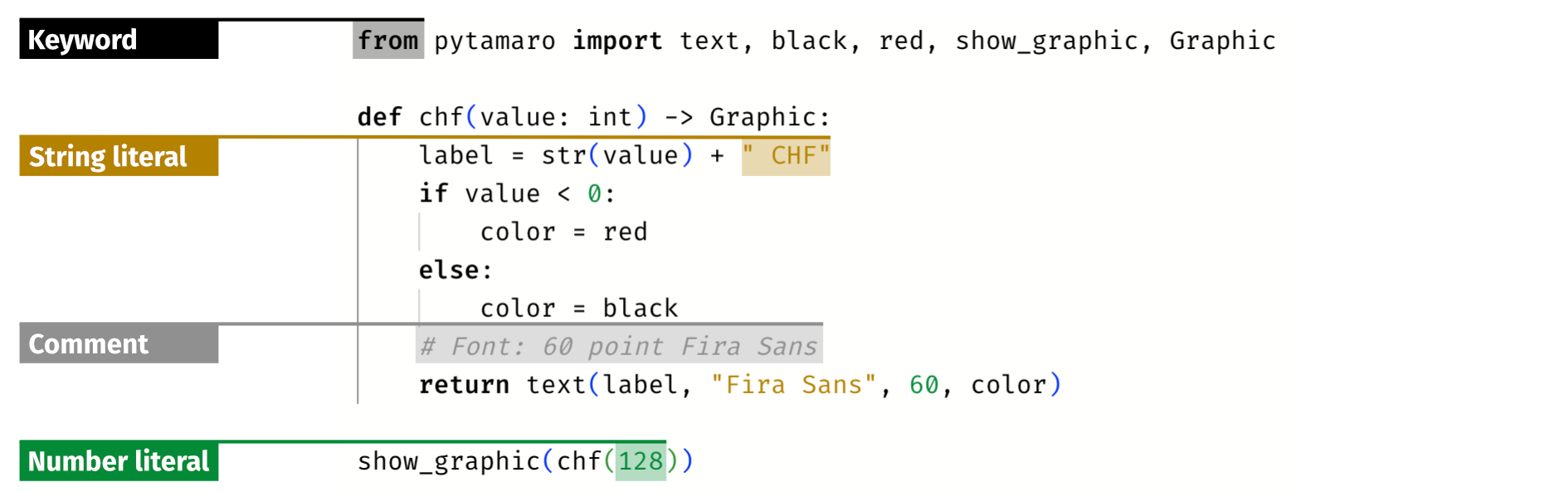

Code Highlighting

Beyond checking for errors, the static analysis in real time also provides the information necessary for code highlighting.

No Analysis

When no static analysis in real time is performed, the editor has no information about the purpose of the different characters making up the source code. It thus shows all the code in the same style: black, in a regular font.

Syntax Analysis

The syntactic analysis provides information that can be used for syntax highlighting. Different kinds of source code tokens are formatted in different styles:

Like number literals, also the None literal and Boolean literals (True and False) are colored in green.

Additionally, the parentheses are colored in different colors, based on their nesting structure in the AST. This allows us to spot matched parentheses more easily:

Semantic Analysis

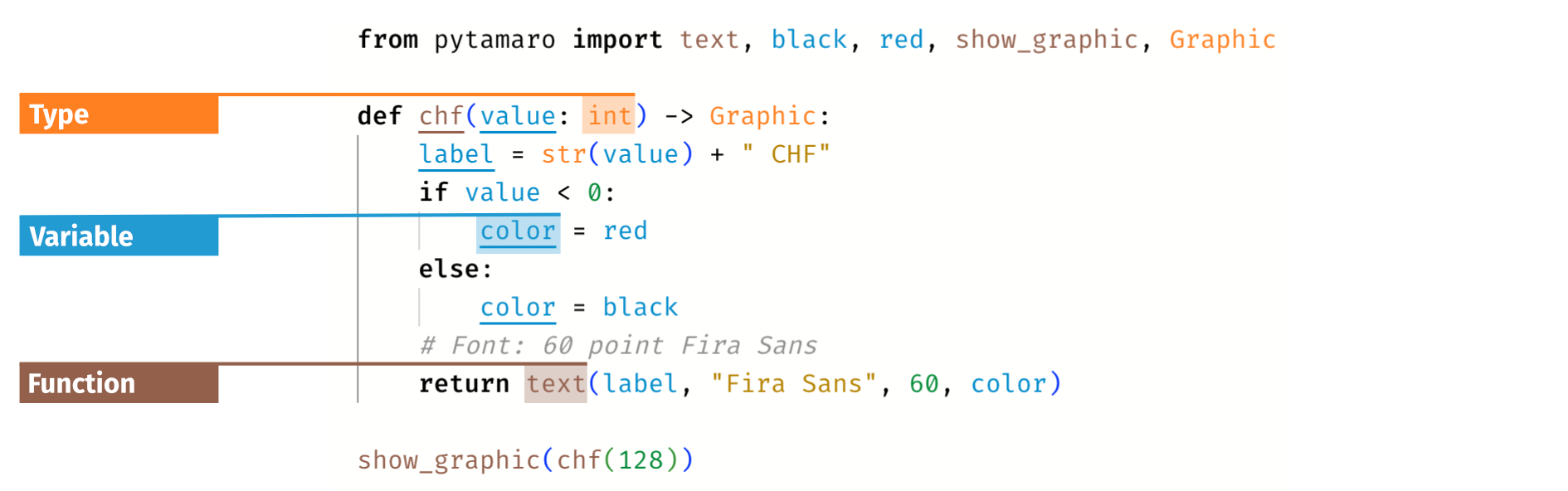

The semantic analysis provides information that can be used for semantic highlighting. Specifically, it provides information about the various names used in the code. This allows using different styles for different kinds of names:

Additionally, the analysis determines where a name is defined (or assigned), and underlines those occurrences. Thus, function names are underlined in all function definitions, and variable names are underlined where they are assigned to.

Configuring Highlighting

Error Categorization

On a conceptual level, in programming languages we can group errors into the following categories:

- Syntax violations of the grammar rules

- Name violations of rules about name definitions and uses

- Type violations of type system rules

- Value violations of evaluation rules

Syntax

Violations of syntax rules can be detected statically, without executing the program. PyTamaro Web reports such violations live, while you are typing. Additionally, if you do execute code that violates the syntax, Python will also report that violation, by raising a SyntaxError.

Name

We see programs as trees. The syntax rules of a language define the proper nesting structure of code.

The naming rules of a language define how one can use names to establish connections between syntactically disjoint pieces of code.

For example, if we define a function, we will want to call that specific function from different places in our program. Thus, we need a way to somehow refer to that function. We do that by giving a name to that function.

This challenge of connecting the place in code where we define something to the place(s) in code where we use it is a general challenge in programming. And it is generally solved by introducing names (also known as identifiers).

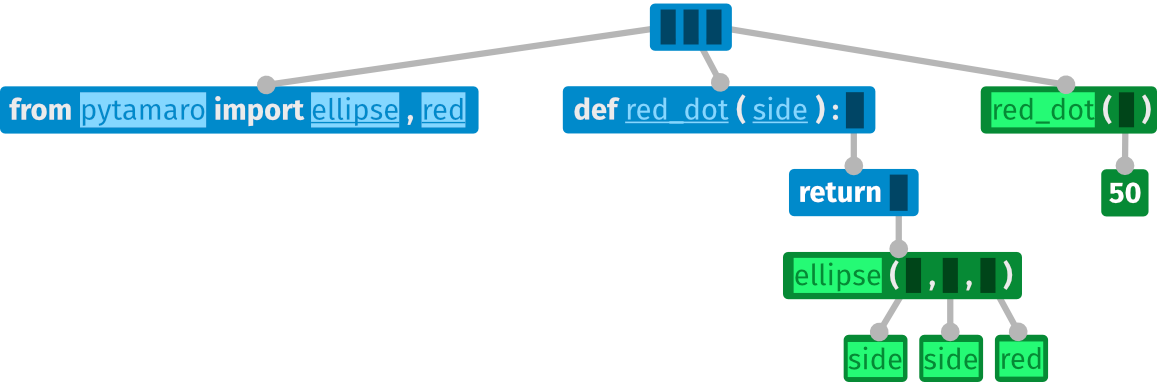

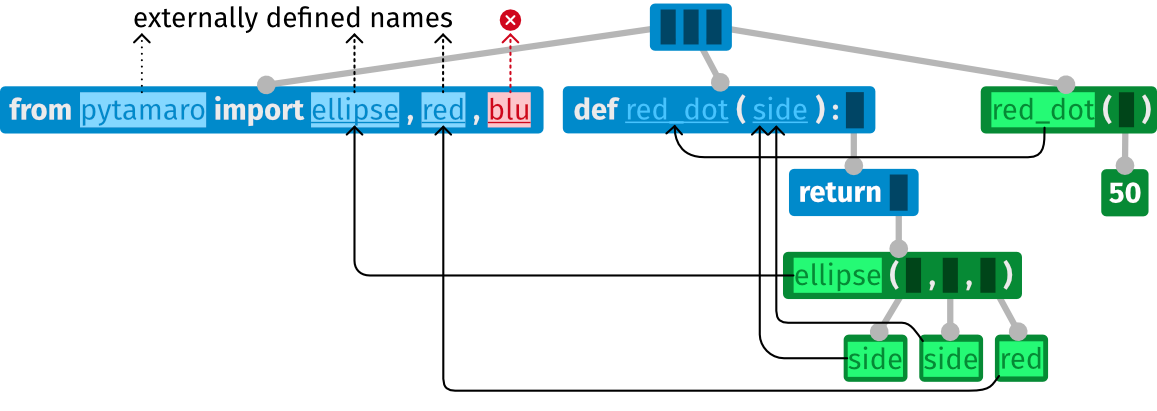

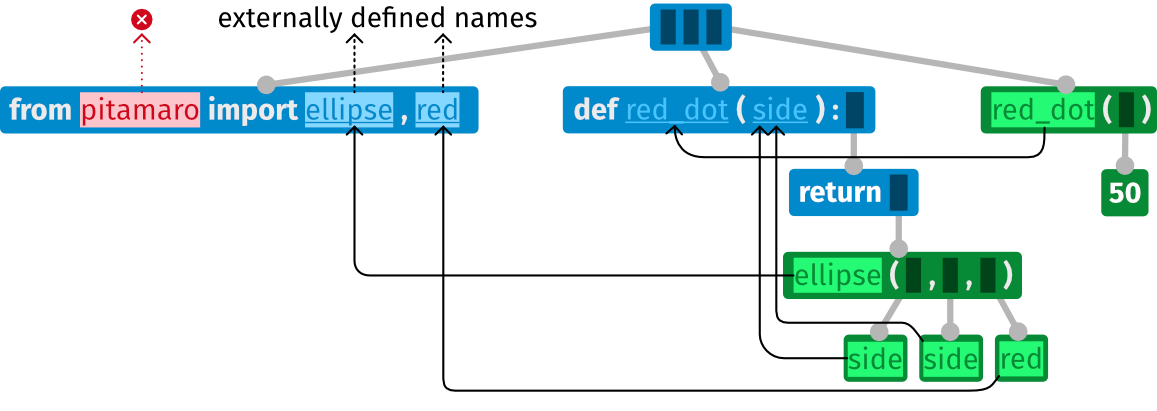

Let's look at the following example program:

from pytamaro import ellipse, red

def red_dot(side):

return ellipse(side, side, red)

red_dot(50)Here is its AST, with nodes in blue (statements) and green (expressions). The edges of the tree (governed by the syntax) are shown with thick lines.

Within the nodes of the above AST, we highlight each use of a name with a bright background, and we indicate each definition of a name by underlining the name.

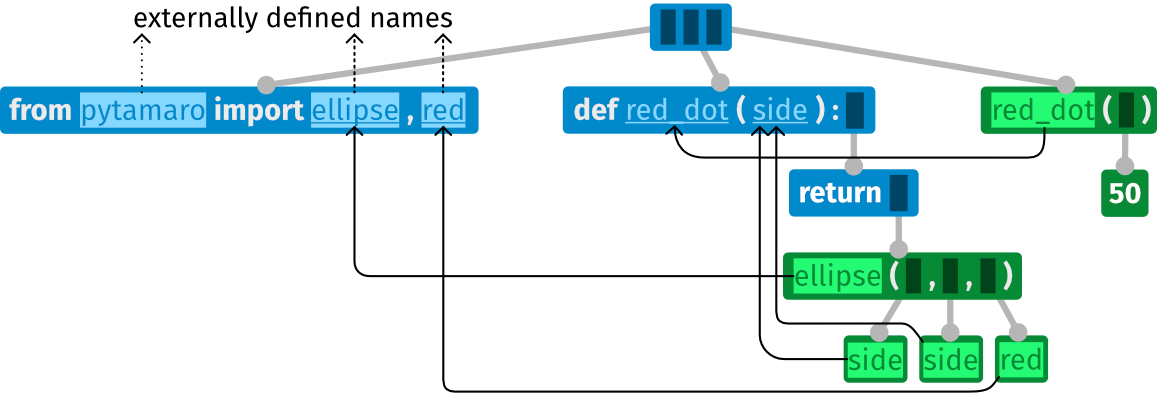

The figure below shows the same AST. However, each name use is connected with an arrow to the corresponding definition (governed by the naming rules in the static semantics).

Each name is defined, either internally (within this AST) or externally

(in the AST of the pytamaro module, which we do not see here).

Besides the names (in color), the AST also contains some other words (in white):

from, import, def, and return.

Python does not allow us to use those words as names.

They are reserved words.

They are keywords of the language

that explicitly appear in the syntax rules.

The use of names in programs can lead to all kinds of errors. We categorize all those errors under the Name category. Let's look at some common examples.

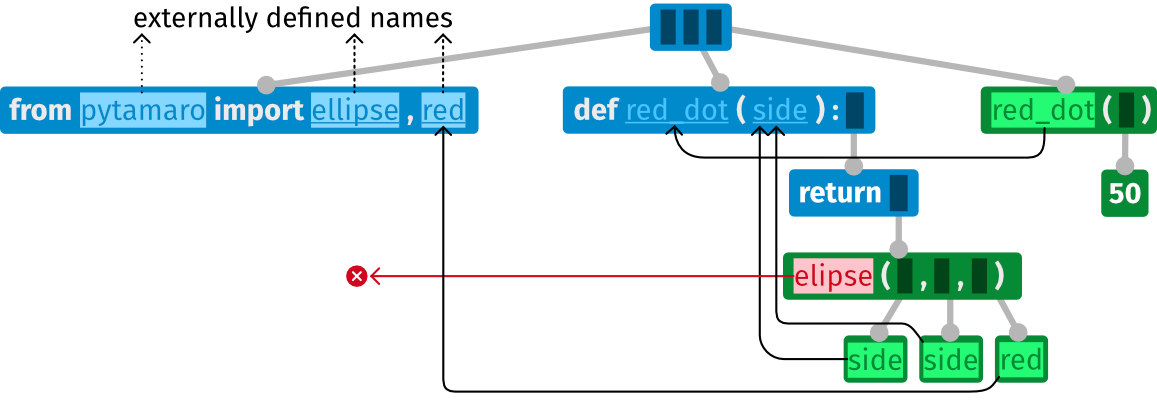

Using a name that has not been defined

The following AST represents a broken program that tries to call a function elipse,

but the name elipse has not been defined

(neither by importing it, nor by defining such a function).

Importing a name from a module that does not define them

The following AST represents a broken program that tries to import the name blu from module pytamaro. The module exists, but it does not define that name.

Importing a name from a module that does not exist

The following AST represents a broken program that tries to import names from module pitamaro.

That module does not exist.

Type

While Python does not have a static type system, it optionally allows developers to annotate variables and function signatures with types. These types can be checked statically, to help developers catch and fix errors early.

If you run code that is not type-correct, this can cause Python to raise a TypeError at runtime.

What are the differences between the type errors shown by static checking, and the error you get at runtime?

- At runtime, you only get one error; as soon as the execution encounters the first error, it stops

- At runtime, type annotations are ignored; this means that type errors may happen deep inside code you may not know (e.g., when trying to perform the multiplication inside the

dotmethod above), instead of happening at the place where your code calls a function you want to use.

Value

The following errors are about concrete values, which have to be checked at runtime:

What You Learned

By working through this page, you learned to:

- distinguish between syntax, static semantics, and dynamic semantics, the three sets of rules defining a programming language

- distinguish between errors reported during editing and errors reported at runtime

- configure PyTamaro Web to perform static error analysis in real time of syntax and static semantic errors

- distinguish between four key categories of errors: Syntax, Name, Type, and Value

If you found anything on this page confusing, don't hesitate to let the PyTamaro Web team know via the feedback button at the top right of the page.

This activity has been created by LuCE Research Lab and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Errors

PyTamaro is a project created by the Lugano Computing Education Research Lab at the Software Institute of USI

Privacy Policy • Platform Version fcb1f6ee (Mon, 09 Mar 2026 15:10:41 GMT)